Australia’s ecosystems face an unprecedented crisis. From rainforests in the continent’s north to the alpine bogs and fens of the alps, ecosystems are being pushed towards collapse.

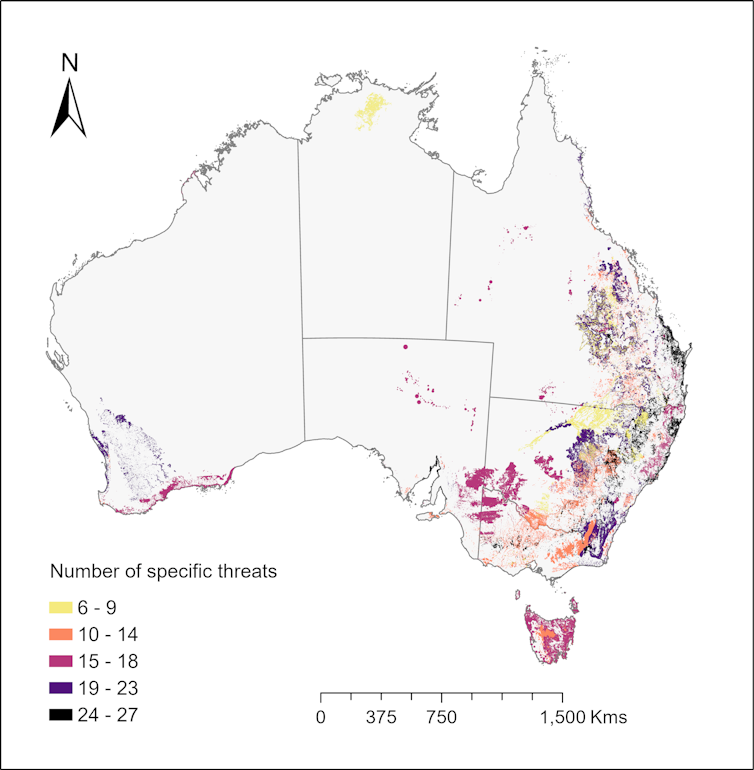

Why? To date, the reasons for declines across all types of ecosystems have not been well summarised. Our new research set out to shed light, providing the first national synthesis of threats to 103 ecological communities listed as threatened under Australian environmental law.

Our study exposed a sobering reality. Our ecological communities face 49 diverse threats, ranging from land clearing and grazing to pollution and changed fire patterns. Many ecosystems face multiple serious threats. Recovery will be complex and difficult – but not impossible.

Australia is renowned for its unique and diverse ecosystems, which are home to species found nowhere else. Every day we delay conservation action, we risk losing more of what makes Australia special.

Jessica Walsh, Author provided (no reuse)

Supporting humanity’s survival

An ecosystem is a complex and dynamic interplay between living and non-living parts, including plants, animals, soil, water and climate. Collectively, ecosystems perform vital processes such as nutrient cycling, cleaning air and water, storing carbon and pollinating plants. Humanity’s survival depends on many of these services.

The terms “ecosystem” and “ecological community” technically refer to slightly different things, but are used interchangeably in conservation management. For accuracy, here we refer to “ecological communities” because these are the entities listed for protection under Australia’s national environment legislation.

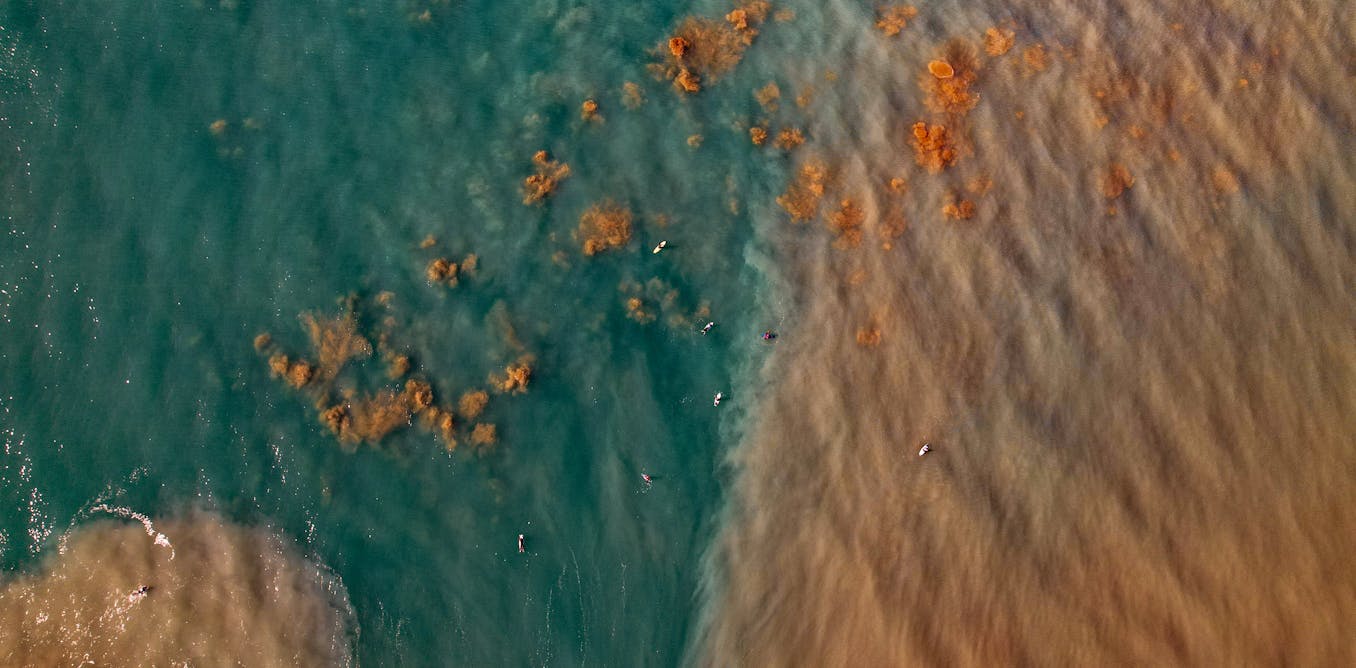

Since European colonisation, Australia’s ecosystems and ecological communities have been under immense pressure. More than 100 are now at risk of collapse. They range from coastal swamp forests, rainforests and vine thickets in Australia’s east, shrublands and woodlands of the west, and giant kelp forests in the south-eastern oceans.

But while the perils facing Australia’s threatened species have been heavily researched, comparatively little is known about threats to entire communities.

We wanted to close that knowledge gap.

Clare Bracey

A perfect storm

We developed a comprehensive dataset of threats to Australian threatened ecological communities – eight broad threat categories and 49 specific threats in all.

We found each community is affected by multiple threats – ranging from six to 27 threats each.

Take, for example, the community known as “White Box-Yellow Box-Blakely’s Red Gum Grassy Woodland and Derived Native Grassland”. It’s dominated by a range of eucalypts, along with several native tussock grass and other plant species in the ground layer.

This ecological community once covered large areas of Victoria, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and southern Queensland. But more than 90% of this has been cleared. It now faces 23 distinct threats in the remaining area, including fragmentation, increased nutrients in the soil from fertilisers and inappropriate livestock grazing regimes.

Meanwhile, the “Alpine sphagnum bogs and fens community” – in southern NSW, the ACT, northern Victoria and Tasmania – also faces multiple threats. These include invasive herbivores, more frequent and intense bushfires, and droughts. Combined, these threats damage fire-sensitive vegetation and peat soils that store water and carbon, and have limited capacity to recover between fires.

Author provided

Nearly all communities are impacted by invasive species and disease, and habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation (99% and 98% of communities, respectively).

Overall, we found 49 different threats affecting the communities we examined. The following were present across almost all, or many, communities:

Jessica Walsh

Where to now?

Our results are a powerful reminder of the severity and scale of the conservation challenges Australia faces. The situation is dire. But our research also points to potential solutions.

Almost all threatened communities could benefit from three key management strategies: habitat restoration, invasive weed management, and improved fire management.

Restoring ecosystems involves reversing damage caused by land clearing and other threats, and replacing vegetation where it has been lost.

Invasive weed management involves controlling or removing plants that out-compete native species for resources or exacerbate other threats such as fires.

In the critically endangered Cumberland Plain Woodland, for example, removing invasive African Olive can help restore native understorey.

Fire management could involve reintroducing First Peoples’ cultural burning practices in some areas or creating ecologically appropriate fire regimes in others.

Importantly, we’ve previously found an overlap between threats impacting ecosystems and species at the same location. This presents an opportunity for integrated, more streamlined conservation efforts.

Shutterstock

Hope on the horizon?

The next steps are clear.

A more consistent approach is needed to identify, document and categorise threat data for ecosystems.

We need a coordinated national approach to restoration, and more funding for on-ground conservation. This would help Australia meet the global goal of restoring 30% of degraded ecosystems by 2030.

Australia also needs stronger environmental protection to prevent further irreplaceable loss.

Finally, we must rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions to do our fair share to tackle climate change.

Australia’s threatened ecological communities are in a critical state. Without rapid and strategic intervention, they will continue to decline. The time for targeted conservation is now.

The post “Scientists counted 49 ways Australia is destroying the ecosystems we hold dear – but there is hope” by Javiera Olivares-Rojas, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Monash University was published on 12/05/2024 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply