Beneath the surface of the Southern Ocean, vast volumes of cold, dense water plunge off the Antarctic continental shelf, cascading down underwater cliffs to the ocean floor thousands of metres below. These hidden waterfalls are a key part of the global ocean’s overturning circulation – a vast conveyor belt of currents that moves heat, carbon, and nutrients around the world, helping to regulate Earth’s climate.

For decades, scientists have struggled to observe these underwater waterfalls of dense water around Antarctica. They occur in some of the most remote and stormy waters on the planet, often shrouded by sea ice and funnelled through narrow canyons that are easily missed by research ships.

But our new research shows that satellites, orbiting hundreds of kilometres above Earth, can detect these sub-sea falls.

By measuring tiny dips in sea level – just a few centimetres – we can now track the dense water cascades from space. This breakthrough lets us monitor the deepest branches of the ocean circulation, which are slowing down as Antarctic ice melts and surface waters warm.

Dense water helps regulate the climate

Antarctic dense water is formed when sea ice grows, in the process making nearby water saltier and more dense. This heavy water then spreads across the continental shelf until it finds a path to spill over the edge, plunging down steep underwater slopes into the deep.

As the dense water flows northward along the seafloor, it brings oxygen and nutrients into the abyss – as well as carbon and heat drawn from the atmosphere.

But this crucial process is under threat. Climate change is melting the Antarctic ice sheet, adding fresh meltwater into the ocean and making it harder for dense water to form.

Past research has shown the abyssal circulation has already slowed by 30%, and is likely to weaken further in the years ahead. This could reduce the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon, accelerating climate change.

Our research provides a new technique that can provide easy, direct observations of future changes in the Southern Ocean abyssal overturning circulation.

Satellites and sea level

Until now, tracking dense water cascades around Antarctica has relied on moorings, ship-based surveys, and even sensors attached to seals. While these methods deliver valuable local insights, they are costly, logistically demanding, carbon-intensive, and only cover a limited area.

Satellite data offers an alternative. Using radar, satellites such as CryoSat-2 and Sentinel-3A can measure changes in sea surface height to within a few centimetres.

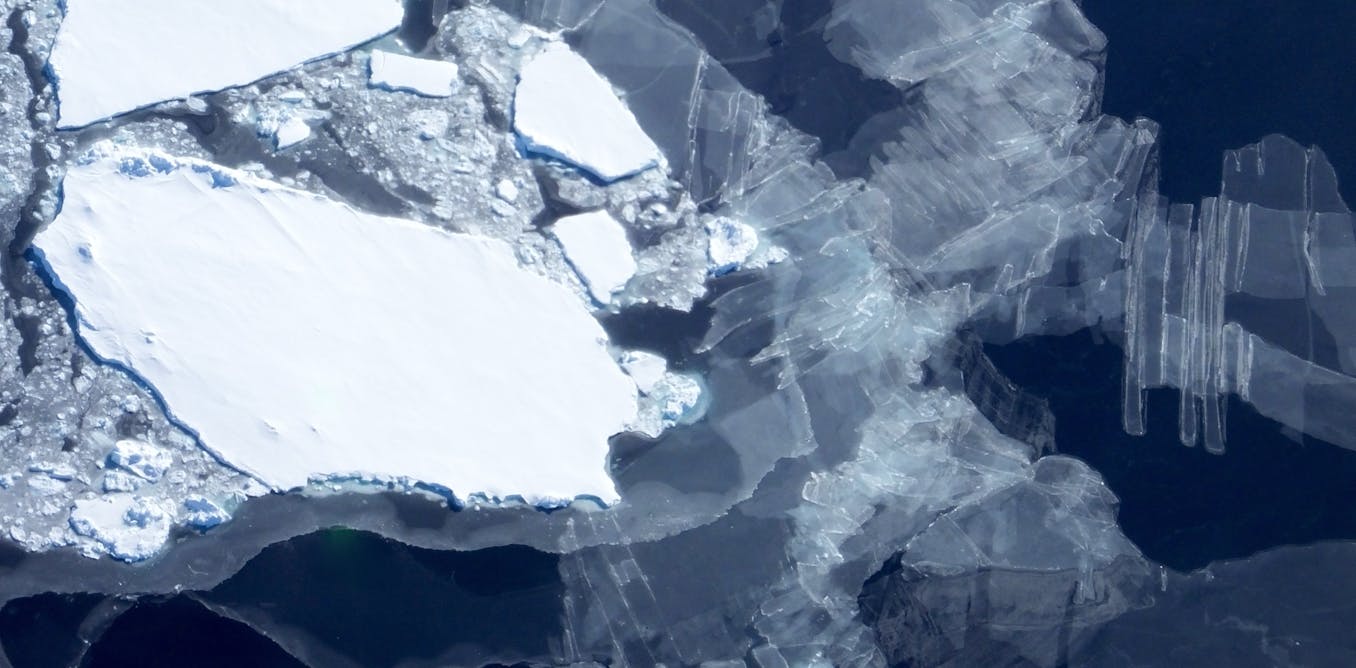

And thanks to recent advances in data processing, we can now extract reliable measurements even in ice-covered regions – by peering at the sea surface through cracks and openings in the sea ice.

NASA ICE via Flicker, CC BY

In our study, we combined nearly a decade of satellite observations with high-resolution ocean models focused on the Ross Sea. This is a critical hotspot for Antarctic dense water formation.

We discovered that dense water cascades leave a telltale surface signal: a subtle but consistent dip in sea level, caused by the cold, heavy water sinking beneath it.

By tracking these subtle sea level dips, we developed a new way to monitor year-to-year changes in dense water cascades along the Antarctic continental shelf. The satellite signal we identified aligns well with observations collected by other means, giving us confidence that this method can reliably detect meaningful shifts in deep ocean circulation.

Cheap and effective – with no carbon emissions

This is the first time Antarctic dense water cascades have been monitored from space. What makes this approach so powerful is its ability to deliver long-term, wide-reaching observations at low cost and with zero carbon emissions – using satellites that are already in orbit.

These innovations are especially important as we work to monitor a rapidly changing climate system. The strength of deep Antarctic currents remains one of the major uncertainties in global climate projections.

Gaining the ability to track their changes from space offers a powerful new way to monitor our changing climate – and to shape more effective strategies for adaptation.

The post “Tiny dips in sea level reveal flow of climate-regulating underwater waterfalls” by Matthis Auger, Research Associate in Physical Oceanography, University of Tasmania was published on 04/22/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply