In all his years studying the life and times of Napoleon Bonaparte, Michael Broers, a professor of European history at the University of Oxford and historical advisor for Ridley Scott’s new biopic, never heard a more succinct assessment of the French emperor than that offered by his friend, Steven Englund. As Englund, an author and journalist, put it: “Napoleon isn’t complicated, but he is multifaceted.”

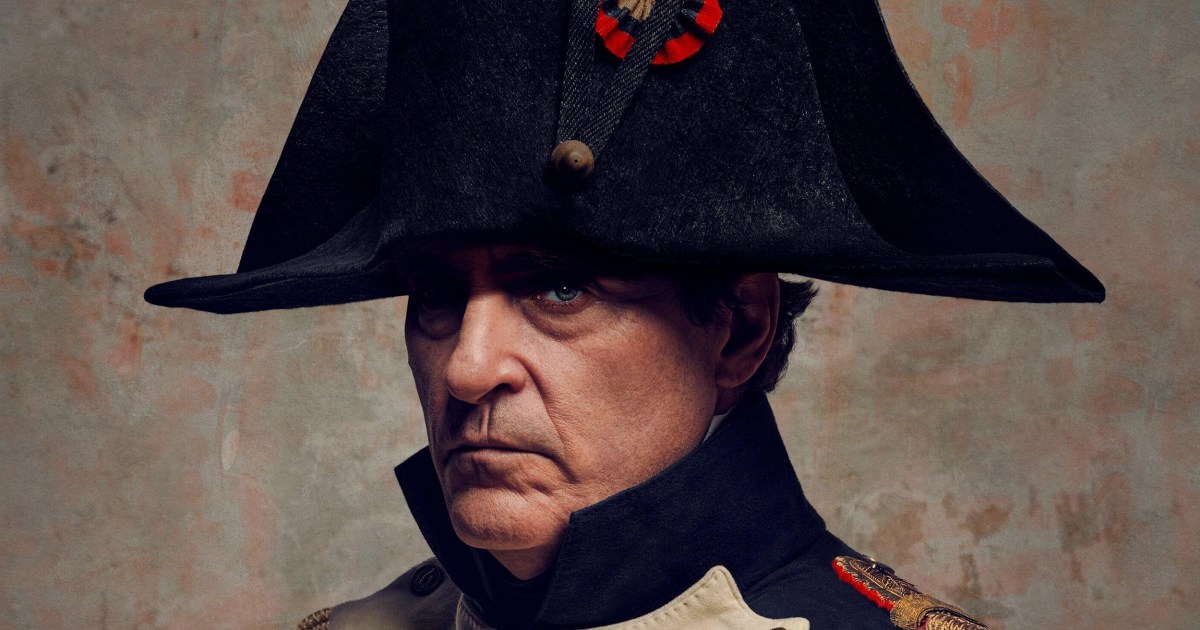

Scott’s Napoleon concentrates on the emperor’s most marketable facets: the lover and military commander. Central to the plot is his complicated relationship with Joséphine de Beauharnais, an aristocrat who knew how to manipulate his pride and insecurities. The clingy and even pathetic version of Napoleon seen behind closed doors is contrasted with the stern and stoic leader that appears on the battlefield — a leader whose conquests rival those of his personal heroes, Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great.

Missing from the film are Napoleon’s lesser-known but arguably more important facets: the magistrate, the reformer, the philosopher, the socialite, and the workaholic, to name a few. Some of these were removed from the film due to time constraints. The emperor’s life was such an eventful one — Broers has written a total of nine books on him so far — that no filmmaker has yet managed to distill it into a single script (though Stanley Kubrick, whose unfinished screenplay is available online, came awfully close).

For instance, Scott does not show Napoleon’s ordinary childhood on the island of Corsica, or the formative years spent at a military academy in Brienne on the French mainland, which he attended on a scholarship. Also absent are Napoleon’s much loved but ultimately less capable brothers and sisters, whom he tried to install on various European thrones.

But some aspects of his life were ignored for marketing reasons. “One of the things I admire most about him was that he was a great man-manager,” Broers told Big Think. “He was a great chairman of committees. He made sure meetings were well-run and everybody had their say.”

When a fellow historian lamented Scott’s disinterest in the nuts and bolts of Napoleon’s governance, Broers said he saw where they were coming from but also that “it doesn’t make for good cinema.” He did note that governance, specifically Napoleon’s relationship with some of his generals, would play a bigger role in the upcoming director’s cut of the film, which is set to be more than four hours long.

Napoleon’s talents as a manager may have also been downplayed because they clashed with the story that Scott set out to tell. His decision to cast Joaquin Phoenix, an actor known for playing emasculated and maladjusted characters in films like Joker and Beau is Afraid, turns the film into a deconstruction of the Napoleonic myth: a look at the flawed, but at times relatable, human being behind the larger-than-life propaganda portraits the emperor commissioned. To show Napoleon as a talented politician may have detracted from the scenes that depict him as a pushover and so they were left out.

Although filmmakers are entitled to take creative liberties, it should be noted that the real Napoleon was indeed a man of contradictions. In private, he often acted like a completely different person than he did in public. Usually, this shift in behavior and mindset was deliberate. “He could focus on a job that needed to be done, a relationship that needed to be confronted — whatever it was,” Broers said.

Those close to the emperor knew and admired this skill, of which he famously said the following: “My mind is a chest of drawers. When I wish to deal with a subject, I shut all the drawers but the one in which the subject is to be found. When I am wearied, I shut all the drawers and go to sleep.”

Napoleon in love

Those who have criticized Phoenix’s emotionally unhinged portrayal of the emperor should read the love letters he wrote to Joséphine. They are mawkish to the point of reading like the poetry of a lovestruck teenager: “Soon, I hope, I will be holding you in my arms; then I will cover you with a million hot kisses, burning like the equator.”

His angry letters, brought on by her infidelity and lack of communication, are similarly childish: “I don’t love you anymore; on the contrary, I detest you. You are a vile, mean, beastly slut. You don’t write to me at all; you don’t love your husband; you know how happy your letters make him, and you don’t write him six lines of nonsense…”

So, while Napoleon’s on-screen relationship with Joséphine comes across as theatrical, it too is rooted in historical fact. Broers defends another part of the film that was met with criticism. Namely, after having an affair, Joséphine has Napoleon admit that without her he is nothing but a brute. Napoleon enthusiasts fume at the suggestion and are quick to point out that he was, on the contrary, extremely well-read, carrying a mini library with him wherever he went.

A fair point, except Joséphine isn’t referencing her husband’s intellect. She’s taunting him over his social status. “I think the line gets to the heart of something he understood,” argued Broers, “that he would appear a brute without her. She knew the aristocracy, and how to run a court. She knew manners, protocol, etiquette. He did not, and he didn’t entirely want to either.”

Lowborn, Napoleon had spent his entire life in the company of noblemen who thought themselves superior. He was bullied at Brienne, whose students hailed from the upper echelons of the ancien régime. Their ridiculing appears to have left scars, and as Napoleon rose through the ranks by the virtue of his merit, he seems to have taken a perverse joy in flaunting conventions. This is evident in the film, where domestic and foreign members of royalty are repeatedly astonished by his directness and (albeit exaggerated) vulgarity.

But directness and vulgarity only got Napoleon so far. Once he took over the country, he needed to learn to play the aristocrats’ game. That’s where Joséphine comes in. “She could be, as it were, the hostess with the mostest,” Broers explained. “She did that for him, and he appreciated it.”

Their power dynamic shifted around 1809, a process started in 1807, when Napoleon met and became intimate with a Polish noblewoman named Maria Waleska. After years of trying and failing to conceive a child together, it became clear that Joséphine was incapable of producing an heir. The revelation came as a shock to both but was especially difficult for Joséphine. As Broers pointed out, with the loss of her fertility, she had also lost the upper hand in the relationship. After their divorce, formalized in 1810, the roles reversed: Joséphine became clingy and Napoleon more distant.

Although the emperor remarried and had multiple mistresses, he remained connected to Joséphine — as depicted faithfully in Scott’s film. They were cordial even in separation, with Napoleon continuing to care for the children she had had by a previous marriage. His final words, uttered as he lay dying of stomach cancer on the island of St. Helena were “France,” “the army,” and, last, “Joséphine.”

This article What the new “Napoleon” film doesn’t tell you about the French emperor is featured on Big Think.

The post “What the new “Napoleon” film doesn’t tell you about the French emperor” by Tim Brinkhof was published on 01/05/2024 by bigthink.com