The Unsung Heroes Fighting Malnutrition | Shruthi Baskaran-Makanju | TED

In the TED talk “The Unsung Heroes Fighting Malnutrition,” Shruthi Baskaran-Makanju sheds light on the often overlooked crisis of stunting in sub-Saharan Africa. She challenges common perceptions of malnutrition by emphasizing the importance of animal-sourced foods, such as meat and milk, in combating stunted growth and underdeveloped young brains.

By sharing stories of pastoralists like Lady Kilena in Kenya and Tes Gabru in Ethiopia, Shruthi showcases the vital role these communities play in sustainable milk and meat production. She calls for a shift in government policies to support pastoralists and bridge the gap between traditional practices and modern solutions.

Drawing on examples from Namibia’s successful reforms in the beef industry, Shruthi highlights the transformative impact of supporting pastoralist economies. She stresses the need for better-quality data to inform policies and investments that can improve nutrition and reduce stunting across the continent.

As Shruthi concludes her talk, she celebrates the resilience and creativity of pastoral communities, expressing hope for a healthier and more promising future for Africa’s children. Through their innovative practices and adaptive mindset, pastoralists have the potential to thrive and pave the way towards a brighter tomorrow.

Watch the video by TED

As a lifelong vegetarian, the last few years of my career came as a surprise to many, but perhaps most of all to my devout Hindu family that reveres cows, when I started telling anyone who would listen: Africa needs more meat, not less. And for one reason: stunting. When you hear the word “malnutrition,”

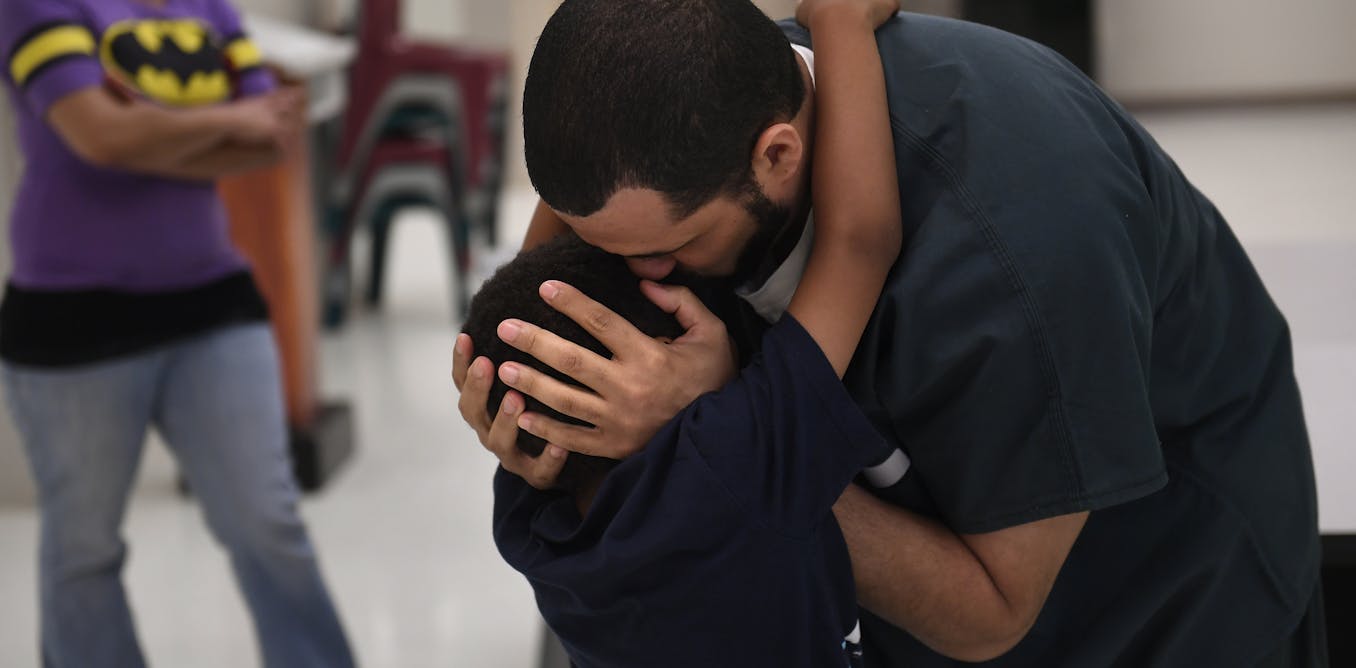

You probably think of emaciated children. But stunting is a quieter crisis characterized by lower height for age. In sub-Saharan Africa, the number of stunted children has increased by almost seven million over the last two decades. And stunting isn’t just about height, though, it’s about underdeveloped young brains.

It makes it harder for children to learn. It makes their health care more expensive due to increased risk of infections, often for the people who can least afford it. In fact, stunting costs Africa nearly 25 billion dollars every single year. It’s holding an entire continent back.

I have been studying agriculture and nutrition issues for over a decade now, and I can say this: there’s no answer to stunting in Africa that doesn’t start and end with milk and meat. Animal-sourced foods offer vital nutrients, like complete essential amino acids, that are hard to obtain from plant-based foods.

African children desperately need these nutrients but struggle to get them. And I can almost hear you thinking: “Isn’t meat horrible for the environment, Shruthi?” And the answer is yes, if we’re talking about the nearly 100 kilograms, astronomical 100 kilograms of meat, that the average person consumes in the West,

Meat that mostly comes from commercial feedlots. When I say that Africa needs more meat, I’m talking about a modest increase from the current average of 12 kilograms a year, meat that mostly comes from Africa’s pastoralists. If I just heard you say in your brain, “Africa’s who?” you’re not alone.

My husband, Bankole, grew up in Lagos, the epicenter of Africa’s largest economy. And as you can see, this man considers a meal without meat an affront to his existence. And yet, when I started working on this topic, he was surprised to learn it was these pastoralists who supplied his favorite ch’arki or tripe. In fact, Nigeria’s nearly 20 million pastoralists own 90 percent of the cattle in the country. But they are also some of the most impoverished communities.

And I’ve been studying pastoral communities, not just in Nigeria but across Africa: who they are, what they struggle with, how they participate in modern livestock markets. And it’s led me to one conclusion. If milk and meat are the answer to Africa’s nutrition challenges, pastoralists are the answer

To how we scale milk and meat production sustainably for the continent. Pastoralists have effectively navigated harsh environments for centuries without GPS or geospatial data. In fact, long before countries even existed. And yet today, the odds are stacked against them as lakes dry up

And the pastures they historically used are fenced off for crop farming, disputes over natural resources are keeping pastoralists locked in a cycle of hardship and poverty. And this is a common story across Africa. Earlier this year, I traveled three hours south of Nairobi to Kajiado County in Kenya,

Where I met Lady Kilena, a 65-year-old Maasai pastoralist. Lady Kilena told me about her first manyatta, a usually circular hut made of grass and cow dung and twigs. And then she pointed to another steel structure on the compound and said that’s what she built with profits from sales of milk.

Yet when I visited her, all of her animals had died during the most recent drought, and she was devastated because her grandchildren had dropped out of school. Efforts to help pastoralists like Lady Kilena have historically been reactive, focused on providing aid during really tough times. But pastoralists don’t want handouts.

They are rational business people with an intuitive knowledge of economics. So instead of trying to force them to settle down and set up commercial feedlots, we need to help them bridge the old and the new by helping companies work more directly with pastoralists, by encouraging governments to pass pastoralist-friendly policies

And invest in better data so that they can thrive in a modern economy and produce more milk and meat without sacrificing sustainability or their culture. One thing is for sure though, we must demand more from businesses. Pastoralists today get taken advantage of by middlemen

Who purchase their animals at half-price or lower in remote rural markets and sell those exact same animals to meat processors in the city for double the price. And this leaves both the pastoralists and the meat processors looking for a way to bridge the gap, not just in distance, but also prices.

I met Tes Gabru, the CEO of Luna Export Abattoirs in Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, last year at his slaughterhouse. And if you’ve ever heard the joke about what happens when a card-carrying vegetarian walks into a slaughterhouse, well, you don’t need to imagine much further, that was me.

Needless to say, I was extremely out of my comfort zone. But I left inspired by Tes’s commitment to use his business as a force for good. Over the last eight years, Tes has been building a program that treats pastoralists as equal partners. He gives them essential support,

Like seeds for fodder or vaccines and access to vets at affordable cost. And then he buys their animals at fair prices and at the right age. And usually that’s around one year, compared to the African market average of four to five years. So you’re saving on four years of grazing on natural resources

And associated methane emissions. Once he buys those animals, he slaughters them humanely. And you can trust me when I say he slaughters them humanely. And he sells that meat, not just in export markets, but also in his own stores in Addis, boosting local meat consumption. That’s a win-win scenario.

Tes hopes that this innovative model is going to double his revenue in two years, sure, but it will also increase pastoralist household income by 5x in just three years. That could rewrite the story of these pastoral economies. In fact, it is already inspiring companies not just in Ethiopia,

But also Nigeria, Kenya and beyond. But Tes and other companies agree the success of programs like that can only go so far as government policies allow them to. And unfortunately, modern policies in sub-Saharan Africa tend to favor farming over herding without recognizing how important pastoralists are,

Not just to the economy but also to society. There are a few forward-thinking African countries that have passed pastoralist-friendly policies. Namibia, for instance, over the last two decades, has rolled out a series of changes. They wanted to prevent medication overuse in animals, so they banned antibiotics and hormones entirely.

They wanted to proactively prevent the spread of diseases, so they instituted a live animal tracking system. And they wanted to improve animal quality, so they put in place animal husbandry practices. The results have been astonishing. After two decades of negotiations, Namibia became the first African country to export beef to the United States.

And it’s not just the US. Namibian beef is reaching South Africa, the EU, Russia, China, too. But let me tell you, the real magic was not in exports or GDP. It’s about how those reforms change the lives of pastoralists. Pastoralists now raise higher-quality animals that they can sell in these premium markets,

And many of them are making up to 2,500 US dollars a year just from meat sales. That’s the average annual income in Namibia. Not just that, they’re also consuming affordable cuts of meat, as well as more milk from their dual-purpose cattle. There’s absolutely no doubt that there’s more work to be done,

Especially in northern Namibia, but this is a much-needed step in the right direction towards reducing stunting and improving nutrition in the country. So why are more countries not following Namibia? If I hear you thinking “data” — bingo, that’s the answer. Pastoralists and their livestock, any data on that is so hard to find.

So hard to find. And what exists is often outdated, inaccurate or simply buried in a stack of papers somewhere in a local government office. And listen, I’m a consultant. I can talk about data gaps for years, but we really need governments to invest in better-quality data.

Otherwise, how are these countries going to navigate to a new destination without a map? And sometimes what you need is a literal map, a map of pastoral migration routes so that countries like Namibia can set up disease surveillance programs. Or a map of livestock concentration

So that business owners like Tes can move their meat processing factories closer to where pastoralists live. And I’m not here to say there’s a silver bullet because there aren’t any. And the history of pastoralists are riddled with neglect and stigma. But I will say

That over the last few years of working with pastoral communities I have been inspired by not just their resilience but also their creativity. Just the other day, I got a WhatsApp message from Tumal, a Kenyan pastoralist that traveled 1,000 kilometers by road to attend a conference I hosted in Nairobi earlier this year.

He was recounting how his wife had ingeniously used cotton, plaster of Paris and acacia tree bark to splint a young camel bull’s fractured leg. The camel is doing great, by the way, he assured me of that. But that resourceful act really shows us that pastoralists are willing to adapt,

To incorporate modern veterinary practices right alongside ancient wisdom. And if we are to support them, to bridge that gap between the traditional and the modern and help them scale up milk and meat production sustainably, I have no doubt that we will see them thrive. And that, in turn,

Can pave the way for reduced stunting and a healthier, more promising future for all of Africa’s children. Thank you.

About TED

The TED Talks channel features the best talks and performances from the TED Conference, where the world’s leading thinkers and doers give the talk of their lives in 18 minutes (or less). Look for talks on Technology, Entertainment and Design — plus science, business, global issues, the arts and more. You’re welcome to link to or embed these videos, forward them to others and share these ideas with people you know.

Video “The Unsung Heroes Fighting Malnutrition | Shruthi Baskaran-Makanju | TED” was uploaded on 03/21/2024 to Youtube Channel TED