For decades, scientists, policymakers, graziers and land managers have been locked in a surprisingly high-stakes debate over what defines a dingo. Are these wild canids their own species? Or are they simply feral dogs?

The intensity of the debate can seem baffling. But the naming of animals influences how they are perceived and managed. The dingo debate has very real consequences for conservation laws, cultural recognition and respect, and the future of one of Australia’s iconic animals.

In 2020, researchers proposed four conditions dingoes would have to meet to be considered separate from domestic dogs: reproductive isolation (they don’t mate and produce fertile offspring), genetic distinctiveness, independent evolutionary path and distinctiveness from South-East Asian village dogs, which superficially resemble dingoes.

In our new research, we lay out the scientific case showing dingoes do indeed meet these requirements, across genetic, behavioural, ecological and archaeological evidence. We now have a clear answer: dingoes are distinct.

Australia’s wild canines have been on their own evolutionary path for thousands of years. As a distinct lineage, they should be recognised in their own right as a species or subspecies. They are not Canis familiaris, the domestic dog. They should be named either Canis dingo or Canis lupus dingo.

Matthew Brun, CC BY-ND

Species aren’t always in neat boxes

One of the greatest challenges for modern taxonomy is how to categorise “species” that don’t fit in neat little boxes but exist along a continuum.

It’s harder still for species whose long and significant associations with humans can lead to substantial changes that are evolutionarily significant.

It’s widely accepted domestic and wild animal populations should be distinguished and be given different scientific names. Domestication is often portrayed as a simple before-and-after event. But this isn’t accurate.

Domestication is a long, messy continuum. Some domesticated species such as cattle and modern dog breeds depend on humans for their survival. But dingoes are different. They have lived alongside people but are also entirely capable of surviving without us, and have done so for thousands of years.

In evolutionary terms, what matters is the trajectory. Did human contact fundamentally alter the appearance, biology and behaviour of the species, locking it into a domestic lifestyle? Or did human influence have little effect, meaning the species has been shaped primarily by natural selection in the wild?

Abuk Sabuk/Wikimedia, CC BY

Do dingoes meet the criteria to be considered taxonomically distinct?

Our research shows how the four conditions have been met to consider dingoes separate:

1. Reproductive isolation

Dingoes have been separated from other Canis lineages for 8,000-11,000 years. Genetic studies show dingoes have little contemporary interbreeding with domestic dogs, even when they live in the same areas. While all Canis species can interbreed and produce fertile offspring, differences in breeding seasons and behaviour act as natural barriers. Unlike dingoes, domestic dogs rarely establish wild, self-sustaining populations.

2. Genetic distinctiveness

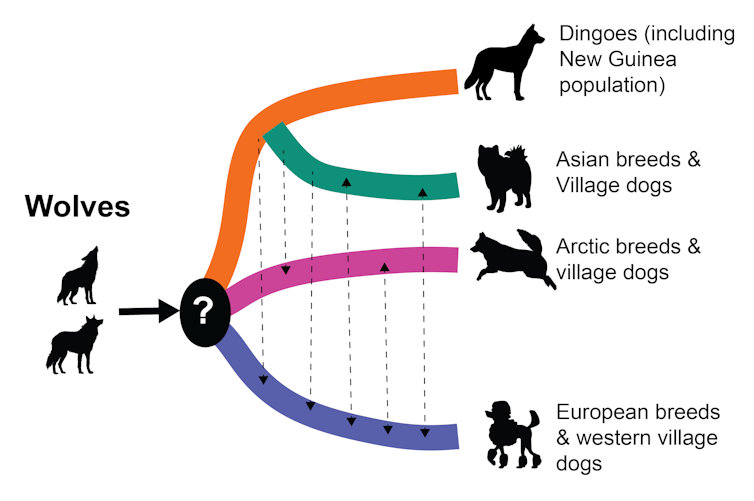

Genome-wide analyses reveal dingoes descend from an ancient “eastern” dog lineage, while most modern domestic dogs come from “western” and “Arctic” dog lineages. Since their arrival in Australia, dingoes have remained genetically isolated.

Kylie Cairns, Author provided (no reuse)

3. An independent evolutionary lineage

From a genetic point of view, dingoes are more distinct from domestic dogs than domestic dog breeds are from each other. Modern dog breeds have undergone waves of mixing and human selection, while dingoes have not. This is why dingoes lack the genetic adaptations to starch-rich diets that domestic dogs evolved alongside agriculture and human contact.

Dingoes have carved out their own ecological niche in Australia’s unique environments, from deserts to snowy mountains. They have developed separate traits such as hyperflexible joints and a single breeding season over autumn and winter. By contrast, humans have heavily shaped the evolutionary path of domestic dogs, making them reliant on us.

4. Clear up whether dogs found in South-East Asia are dingoes

Some researchers have suggested dingo-like village dogs in South-East Asia are actually dingoes. While dingoes share some ancestors with these dogs, modern genetic evidence shows dingoes and their closest relatives, New Guinea singing dogs, are a separate population.

What’s in a name?

The question over how dogs evolved is not yet resolved. Some taxonomists believe dogs are a subspecies of wolf, while others disagree. Given this uncertainty, giving dingoes a unique scientific name can be done in two ways.

If we consider dingoes distinct from both dogs and wolves, the most appropriate name would be Canis dingo — recognising the dingo as its own species with a long, separate evolutionary history.

But if dingoes are not distinct from wolves, the correct name would be Canis lupus dingo. This would treat it as a subspecies of wolf, while still acknowledging its wild lineage separate to domestic dogs.

The name of the dingo matters

There is real power in the name of a species.

Under some state laws, dingoes are defined as “wild dogs”. This means dingoes are targeted for lethal control – even in many national parks. If treated as a domestic dog, dingoes can be ineligible for official threatened species lists.

As a result, the species is often overlooked for targeted conservation, while its culturally significant role for many First Nations peoples is often not recognised nor respected.

Defining dingoes as a distinct species or subspecies would allow governments to differentiate them from domestic dogs in laws, policies and conservation programs, and align western science with First Nations knowledge holders who have long distinguished between dingoes and dogs.

Big Desert Dingo Research, CC BY-NC-ND

Ending decades of confusion will take work

To clear up long-running disagreement over the dingo, we believe the time has come for an independent, evidence-based review by a national scientific body. This would bring together geneticists, ecologists, taxonomists and First Nations representatives.

This approach helped untangle similarly knotty problems overseas, such as the United States National Academies’ review to settle the taxonomy of red and Mexican wolves.

An Australian review could finally end decades of confusion for the dingo and ensure our laws reflect the most up-to-date scientific evidence.

Taxonomic debates might sound obscure. But this naming question will shape the future of one of Australia’s ecologically and culturally significant animals.

We believe the evidence shows the dingo is not a domestic dog – it’s on its own path. The question is whether Australia can accept this evidence.

The post “Dingoes are not domestic dogs – new evidence shows these native canines are on their own evolutionary path” by Kylie M. Cairns, Research fellow in canid and wildlife genomics, UNSW Sydney was published on 08/21/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply