We’re incessantly bombarded with information — from media sources, influencers, advertisers, AI assistants, co-workers, and more. Do you ever feel like there is too much to handle? As if the din makes it difficult to settle your mind, determine truth from falsehood, or even make simple decisions?

Timothy Caulfield, a leading science communicator and the research director of the Health Law Institute at the University of Alberta, admits to suffering from information overload as well. Still, it’s his job to wade into the media muck and suss out what’s real from what’s full of misinformation. For that, Caulfield relies on science.

“Well done and trustworthy science is the essential guidepost for our chaotic information ecosystem. Without it, we are lost,” he writes in his new book, The Certainty Illusion: What You Don’t Know and Why It Matters.

But science is frequently exploited and misused to pull the wool over our eyes. Other fundamental guideposts, such as our sense of goodness and the opinions of others, can also be twisted through deceit. In The Certainty Illusion, Caulfield’s aim is to expose how those guideposts get corrupted and to help readers rebuild and protect them.

Big Think recently spoke with Caulfield about his new book, his many years of combating misinformation, and his favorite Star Wars movies. What follows is a transcript of our interview, edited for length and clarity.

Big Think: You argue that three main illusions fool us: the science illusion, the goodness illusion, and the opinion illusion. Can you briefly describe these?

Caulfield: The science illusion is this idea that because science is viewed — I think rightly — as the best way to understand our world, its value has increased. Moreover, our craving for clarity and certainty has increased the value of scientific language.

In the book, I joke about how The Enlightenment has won — but mostly as a brand, not necessarily in substance. Everyone says “my product has more science” or “is scientifically proven.” Because science is so valuable in the current marketplace of ideas and attention economy, it gets manipulated. It’s the illusion of science, not real science.

The goodness illusion goes to the core of a lot of important themes in the book. Because our information environment is so chaotic and noisy, we crave clarity and certainty. We want clear signals about doing what’s right for ourselves, our family, and our community. The market knows that, so it provides us with these signals. Health halos are the best example, words like organic, natural, and non-GMO. [These] are meant to be a shortcut for decision-making and make it easier for us to take a path towards goodness — even though the illusion of goodness doesn’t really represent what the science says, which is invariably more complicated and nuanced.

Lastly, the opinion illusion. We crave expert advice; therefore, opinions have been commodified and marketized and weaponized. One of the best examples are the reviews we see online. I picked that topic because everyone can relate to it and it feels less weighty, but it is a big issue! Trillions of dollars in the world economy are nudged by reviews. Because opinions are so valuable, they are being manipulated. It is a good example of the forces in our information environment that are deluding us. We want clarity. We want truth. But it’s rigged to deceive.

Big Think: You write that it’s getting more difficult for us to be certain about anything, even though we have access to more information and opinions than ever before. At the same time, social media algorithms and self-selected media sources feed us information that conforms to our beliefs.

Do you also think this unprecedented information-sorting machine makes it easier for people to feel more certain than ever?

Caulfield: Spot on. So many entities want to give the impression of certainty and make you feel like you’re certain. There is some research to suggest that humans crave that. That’s one of the reasons that conspiracy theories take off. We want order in our world, and sometimes, especially in science, things are just uncertain or random. There’s no magical force that provides that certainty.

There is an ongoing tension in our information environment. On the one hand, the algorithms are rigged to play to our rage, emotions, and cognitive biases in ways that confirm preconceived notions — to provide that sense of certainty. But it’s an illusion! They are constantly trying to destabilize us, to create distrust.

In some ways, there’s this intention to play with the uncertainty out there. We know that social media companies are making money off misinformation. A lot of studies have shown this. Rage, misinformation, things that play to your negativity bias — they’re gonna get more clicks and be shared more frequently.

Big Think: Can you explain what you mean by “scienceploitation”?

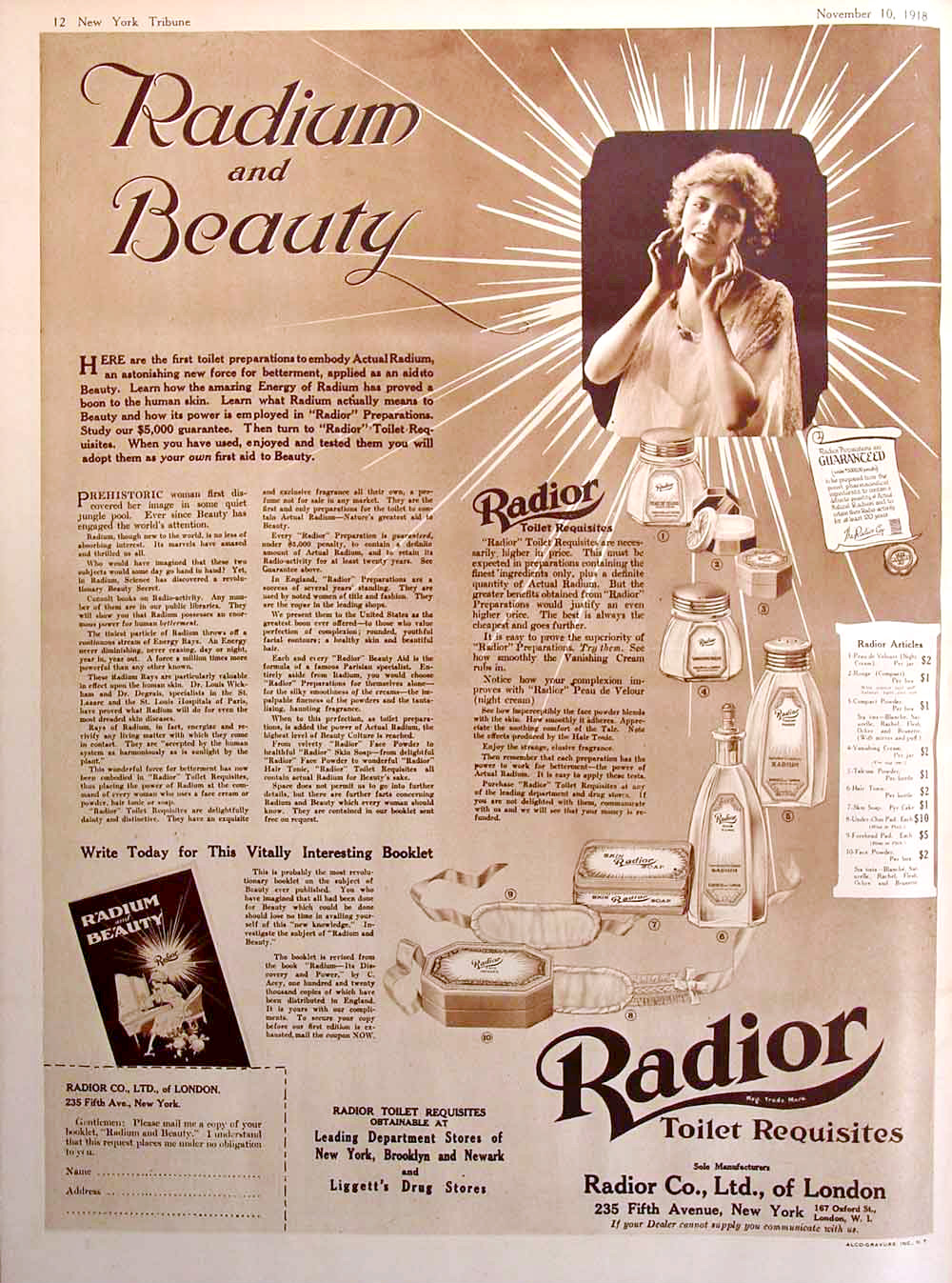

Caulfield: “Scienceploitation” is taking a genuinely exciting area of science and exploiting it to sell products, brands, even ideology. Historically, it’s not new. One of the best examples is when radioactivity burst onto the scene. We started to see radioactive products [like makeup] being rolled out. We know it’s a strategy that works and works well.

Fast forward to now: It’s accelerated. It’s everywhere, absolutely everywhere, especially in the health, beauty, and wellness space. You even see influencers online using science-y terms like “quantum” to support absurd ideas. You sprinkle in that science-y language, and it has a big impact.

Big Think: What is an egregious example of scienceploitation today?

Caulfield: Stem cells is a good one because the phrase has taken on a life of its own. It now represents “cutting edge,” “exciting,” “regeneration,” etc. Despite all the hype and excitement, very few stem cell interventions truly work, yet clinics everywhere are selling unproven stem cell therapies. There are skin creams and shampoos that use the phrase.

My other favorite example of scienceploitation is the microbiome. Maybe just seven or eight years ago, most people would only be vaguely aware of what the microbiome is. Now it’s everywhere. People just assume it’s a signal for “good for you” even though the science doesn’t support that.

List any big science movement, and you’ll see an adjacent scienceploitation industry.

Big Think: You write that humans process an estimated 74 gigabytes of information every day. Neuroscientists Sabine Heim and Andreas Keil noted that 500 years ago, “74 gigabytes of information would be what a highly educated person consumed in a lifetime, through books and stories.” I’ve never seen our era of information overload quantified in such a clear way.

How can our brains possibly keep up with this bombardment of data? Evolutionarily, it seems we’re generations behind.

Caulfield: I don’t think [our brains] can. A recent study shows that 74% of shared headlines on social media aren’t clicked through. That is a product of how noisy our information environment is. People are searching for simple paths through this noise, and that need is being exploited.

Big Think: Did you learn anything from writing The Certainty Illusion that surprised you?

Caulfield: I was surprised at the data behind online reviews. I didn’t realize there was this rich literature. I found it fascinating. I was surprised by what the research said about how incredibly persuasive online reviews are. People trust these reviews more than they do their family and friends.

I love this quote from a comedian who made a fake restaurant. He said that people trust a review more than the food in their own mouths.

Big Think: I’ve covered a lot of pseudoscience in my career, but you’ve explored more hokum than me. Even I was flabbergasted by your account of watching a woman get apple stem cells injected into her skin as a beauty treatment. Does anything stand out?

Caulfield: Oh my gosh, so much. Drinking urine is a big one. I stood next to a guy who — hot off the tap — filled up a bottle of urine while I was interviewing him and chugged it.

Big Think: What was the supposed benefit of that?

Caulfield: It’s supposed to help your masculinity and increase your testosterone. Tasting it is also supposed to let you know if you’re eating properly. He was naked when he did it, by the way, which added to the ambience. Completely absurd.

I’ve gone to so many of these different kinds of providers all over the world. I’ve had the opportunity to try different alternative therapies and wellness routines. I’ve found that almost without exception, it’s been a positive experience. I think that’s important to know. I get it. Often it feels good. I definitely get the idea of the “placebo theater,” and my experiences in the conventional system have not been great. I think I’m much more open-minded to it now.

Big Think: Early in your book, you share a personal story about a man who angrily confronted you after you gave a public lecture about the spread of health misinformation. “Science is full of shit,” he told you. How did you handle that situation then?

Caulfield: I started rolling out more studies. That’s not always a good idea …

Big Think: That’s funny. He just told you “science is full of shit,” and you started rolling out more science.

Caulfield: Right? I study science communication. I know about the deficit model! I know that bombarding people with more facts won’t cut it.

I give a lot of public lectures, and for some reason, this one stood out. I can remember him walking away, not satisfied with what I said. I can remember that. It really did hit me.

Big Think: If you had a chance again with this gentleman, what would you do differently? I’m sure you’ve thought about it.

Caulfield: I would try to talk about the nature of scientific inquiry — why science is “full of shit” and why I think these studies are more credible.

It also speaks to the idea of a body of evidence, scientific consensus, and what consensus is. It’s not a memo that comes from the Star Chamber or big pharma or biotech. It’s messy. It’s contested. It’s always evolving. It’s thousands of independent studies kind of pointing in a particular direction.

So, I think the world needs more scientific literacy on those topics and the inherent nature of how messy science is and how hard it is. I think that also helps people guard against hype, overpromise, and scienceploitation.

Big Think: In many ways, your book comes off as an evidence-based self-help book, guiding readers how to suss out good information amidst all the static and noise. In my opinion, many self-help books are a waste of time, touting outright pseudoscience or spreading armchair psychology nonsense. Your book refreshingly does neither of those things! I’m curious if you share my sentiment. If so, any thoughts on why so many self-help books are BS?

Caulfield: I totally agree with you about self-help books and about the whole self-improvement industry. I find it extremely frustrating. It’s trying to provide overly simplistic solutions to fantastically complex human problems, and they do use pseudo-profound bullshit too often. That happens in the whole wellness industry. They really are exploiting people’s desire for clarity and certainty.

We want order in our world, and sometimes, especially in science, things are just uncertain or random. There’s no magical force that provides that certainty.

Timothy Caulfield

Big Think: At the end, you offer an in-depth list of steps we can take to suss out good information in a time of information chaos. If you could pick out one tip — because people like self-help books — that we could adopt quickly, what would it be?

Caulfield: The power of “the pause.” Gordon Pennycook and David Rand from MIT, who I interviewed for the book, have done interesting work that shows if you just pause for a moment when you see something on social media or online in-general, it really makes a difference. It’s not perfect, but it moves the needle.

Big Think: Now, the real meat and potatoes: In the book, you snuck in your ranking of the Star Wars movies. “Correct answer: 5, 4, 7, 8, 6, 3, 9, 2, 1,” you wrote. I won’t ask you to justify each one, so I’ll simply ask why you rank The Phantom Menace in last place rather than The Rise of Skywalker, which is the worst in my mind.

Caulfield: I don’t take this list lightly. My 28-year-old son is a radiologist and a Star Wars scholar. He agrees with you. But the Jar Jar Binks thing in Episode 1 … I just can’t get past that. I also can’t get past how clunky it feels. Episode 9 is terrible, although it has some impressive visuals and moments.

I think it’s more controversial that I put Episode 8 in front of Episode 6. I know the Ewoks represent the Viet Cong defeating the United States, but it just ruined the vibe and tone of the series. I also think Episode 3 is great. I could arguably bump it up, but I am open to this debate!

This article Exploring the wild and disturbing world of “scienceploitation” is featured on Big Think.

The post “Exploring the wild and disturbing world of “scienceploitation”” by Ross Pomeroy was published on 02/13/2025 by bigthink.com

Leave a Reply