Competitive swimmers know that swimming underwater causes less drag resistance than swimming at the surface. Splashing around making waves isn’t the most efficient way to swim. Any energy spent creating waves is essentially wasted, as water is moved without providing forward thrust for the swimmer.

New research by my colleagues and I has found evidence that many air-breathing marine animals know this too – or rather they have evolved swimming behaviour that minimises wasted energy on long journeys.

We know a lot about how birds save energy on their migrations, such as flying in V formations, riding updrafts, or timing their departure for favourable winds. But it has been challenging to study these kinds of adaptations in marine animals, which are largely hidden from view, particularly during long-distance travel.

Whales and sea turtles, for example, often travel thousands of miles to breed or feed. These animals have evolved to minimise the energy costs of such long journeys, allowing them to conserve energy for reproduction and survival.

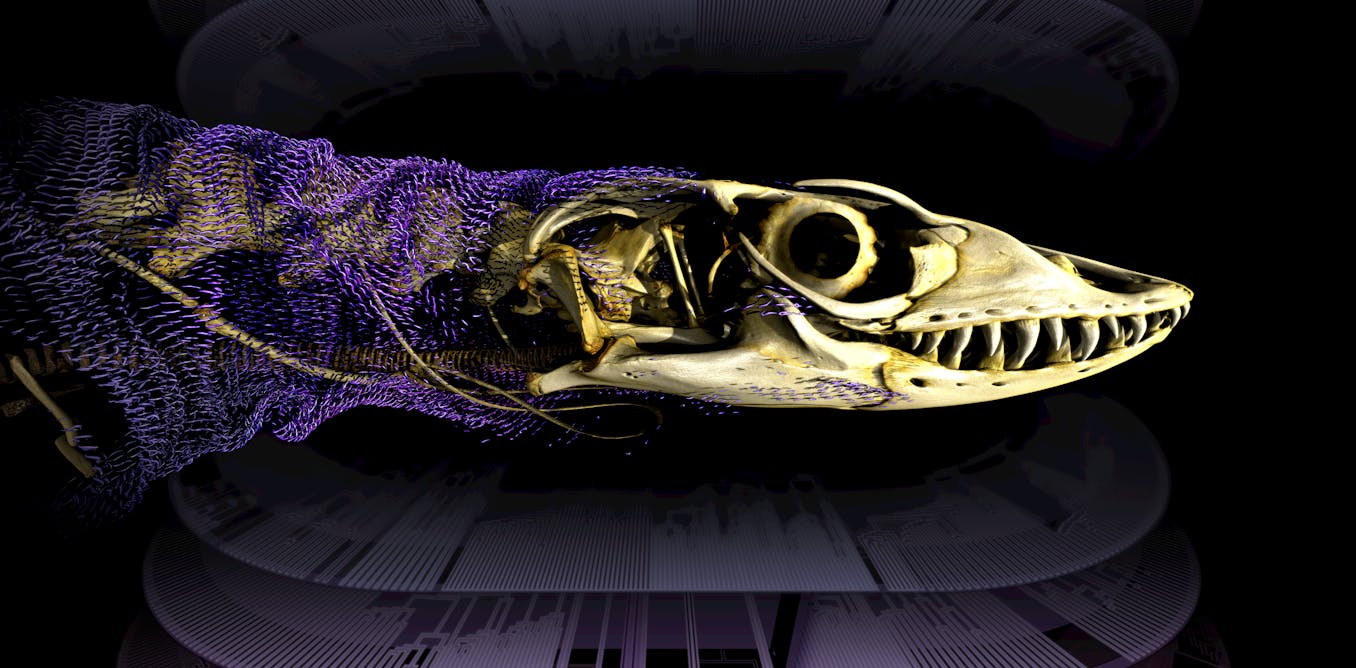

Using Fitbit-style accelerometer data, depth-loggers and video footage from animal-borne cameras, we collected detailed swim-depth measurements in free-living little penguins and loggerhead turtles. We compared these with satellite-tracking depth data for green turtles on long-distance migrations, and published data from whales, other species of penguins and migrating sea turtles from other populations.

Optimal depths

What we discovered was a remarkable similarity in relative swim depth across sea turtles, penguins and whales. When these air-breathing animals are travelling rather than feeding or evading predators, they swim at near-optimal depths to minimise energy waste. They swim just deep enough to avoid creating waves at the surface but not so deep that they expend extra energy travelling up and down to breathe.

This sweet spot for energy efficiency has long been established in physics. Experiments show that “wave drag” – additional drag from wave creation – is minimised once an object is at a depth of three times its diameter. For swimming animals, this diameter refers to their body thickness from back to chest.

Our research revealed that many marine animals, from little penguins (about 30cm long) to pygmy blue whales (nearly 20m long), travel at depths of around three body thicknesses under the surface. This shared strategy helps them save energy on their epic journeys across the oceans.

These findings are especially exciting because they span such a wide range of species, from birds to mammals and reptiles. They also have important implications for conservation. Knowing where animals travel and at what depths can help us design better conservation measures to protect them.

For example, understanding typical swim depths could help reduce the risk of boat strikes, which are a major threat to whales, or decrease accidental captures in fishing gear. Tracking animals to find out where they live and travel has become a key part of designing effective conservation measures. For marine animals, considering swim depth – essentially adding a third dimension – can also help to inform strategies to provide better protection.

Kimberley Stokes, CC BY

Of course, not all swim depths are determined by energy efficiency alone. Animals may dive deeper to hunt for prey or avoid predators. But during long-distance migrations or shorter “commutes” to feeding areas, this energy-saving pattern emerges across many air-breathing species.

Collecting depth-tracking data from migrating animals has been notoriously difficult, but advances in technology are making it easier. We are thrilled that our work has contributed to uncovering this widespread adaptation, and we believe there will be much more to learn as tracking tools improve.

Historically, depth-tracking tags have prioritised recording the deepest and longest dives. They are often seen as the most dramatic or impressive aspects of animal dive behaviour. Our research highlights the importance of near-surface tracking too. This “ordinary” behaviour of swimming at just the right depth is no less impressive, given the energy savings it enables over vast distances.

The post “how marine animals save energy on long journeys” by Kimberley Stokes, Research Officer in Biosciences, Swansea University was published on 01/30/2025 by theconversation.com

![Animals vs. Water: Hilarious Moments! 😂 [2025 Edition] – Video Animals vs. Water: Hilarious Moments! 😂 [2025 Edition] – Video](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/F1_AvAuQI5M/maxresdefault.jpg)

Leave a Reply