Younger generations today mainly knew Donald Sutherland in his grizzled paternalistic roles, by turns loveable (as in Pride and Prejudice) or hateful (as in The Hunger Games).

But older moviegoers like myself came to know and love him in the cinematically dynamic ’70s, when he hit the scene as an “oddball” Hollywood outsider, with a charisma that was hard to pinpoint, but endlessly compelling.

The nickname “Oddball” came from his character in Kelly’s Heroes (1970), but it was really a catch-all term for how he was too politically engaged, or too aesthetically complex in his acting approach, or even just too sexually uncategorizable.

As my scholarship has examined, what stands out in Sutherland’s performances, interviews and most commentaries about him was a sort of practice of “self-loss” in all aspects of his persona. Whether engaged in acting, activism or acts of intimacy, he brought an element of surrender, self-effacement and vulnerability to his performances through the ’70s.

Sutherland was always “subjecting” himself to something else: a cause, a companion and maybe most interestingly, his directors.

His work in the ’70s covered three phases: his early movement-based political years (which included his love affair-comradeship with Jane Fonda); the British and European “auteur” years; and a shift to the “ordinary” as corporatism ushered in the 1980s.

1. Movement-based political years

In M*A*S*H (1970) and Kelly’s Heroes, Sutherland played the man’s man for a broad sector of the white male middle class, with his deeply felt outrage at the world’s injustices and a flair for humorous jibes at conformists.

But he also appealed to the middle-class liberated woman, and could even serve as possible model for romantic partnership — a helpmate willing to subject himself to a woman’s lead, as in An Act of the Heart (1970), Klute (1971) and Don’t Look Now (1973).

He offered all the intellectual left-wing politics of a Norman Mailer without the male chauvinism.

His political-activist phase was significantly linked with women who took the initiative, and for whom he played the helpful sidekick. While Alan J. Pakula’s Klute wasn’t about the Vietnam War, Sutherland and co-star Jane Fonda were coming to be known as America’s most high-profile anti-war celebrity couple of the year, dogged by the FBI’s COINTEL program.

Read more:

Donald Sutherland’s off-beat, counter-cultural roles reflected his leftwing politics

Sutherland and Fonda headlined F.T.A. (Free, or Fuck, the Army), a documentary film based on an anti-war review composed of songs, sketches and visual gags.

It was pulled from circulation before very many people could see it, but was a prime example of Sutherland’s experiment with self-effacement in the service of the troupe and the troops.

2. British and European “auteur” years

Sutherland next turned his attention inwards to the historical forces that produce the very self which speaks truth to power. In this period he worked with British and European auteur filmmakers such as John Schlesinger, Bernardo Bertolucci and Federico Fellini.

Under their directorship, Sutherland lent his star status to a series of projects dissecting fascism in its various forms. He read The Mass Psychology of Fascism, in which psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich argued that fascism must be understood, not as “the dictatorship of a small reactionary clique,” but as “an international phenomenon, which pervades all bodies of human society of all nations.”

(Wikipedia)

With Bertolucci and Fellini, Sutherland took the most uncanny plunge into the realm of the fascist within. Sutherland brought his copy of Reich’s book to Bertolucci’s set for the film 1900, where he was to play Attila, the film’s quintessential fascist in the context of the class struggle in Italy.

He wanted to “create a character who you would look at and go, ‘But for the grace of God there go I.’” But Bertolucci’s concept of the character was so grotesque that few would be able to connect with Attila’s utter sadism. Sutherland wasn’t to find a fellow Reichian for another decade, when in 1985, Kate Bush persuaded him to play the controversial anti-fascist in her music video Cloudbusting.

Where Fellini was concerned, this time it was more like a sadomasochistic relation between actor and director, involving erotic pleasure on both sides. Sutherland would spend three hours in makeup, as Fellini had him literally molded and painted to resemble a cartoonish figure of Casanova tacked up on the wall.

Fellini’s comically unflattering characterizations of Sutherland’s physical appearance proved infectious, prompting critics of the film to join in with their own fanciful impressions of the actor. Critic Costanzo Costantini called Sutherland’s Casanova “a bald, glabrous, waxen beanpole, covered with powder and oil, filthy and stinking.”

While Fellini appeared to despise this turd of a Casanova — the better to work out his own antipathy towards fascism — Sutherland sought to love himself as Casanova, to believe himself a beautiful creature, despite all the humiliating abuse he was taking, not only from his director, but also from critics.

Canadian and ‘ordinary’

In the late ’70s, though Sutherland continued to speak out on political issues, the impact of his politics on film seemed limited to efforts to boost the Canadian film industry.

Interestingly, if Sutherland counted as an American commodity in Europe (when it came to securing U.S. financing for Italian films, for instance), by the late ’70s, it was suddenly Sutherland’s Canadian birthright that could be deployed when seeking the newly instituted Canadian tax break offered to projects that could be certified as Canadian.

Sadly, this policy was often exploited by unscrupulous producers or brokers for movies that never even made it to theaters. But long before the new tax law was instituted, Sutherland had regularly returned to Canada to lend his star status to Canadian projects.

For the most part, he chose films that portrayed some aspect of Canadian culture, politics or history that audiences might not otherwise know about, as with Alien Thunder (1974), a dramatization of a conflict between the RCMP and the Cree, set in rural Saskatchewan shortly after the Louis Riel rebellion. The film also starred Gordon Tootoosis.

Read more:

Louis Riel’s trial from 135 years ago continues today with competing cultural stories and icons

Sutherland also played Norman Bethune in a biopic that brought this pioneering Canadian doctor’s involvement in the Chinese revolution to Canadian television audiences.

However, it was in Chicago that Sutherland was to make his big comeback for American fans, with a return to a quintessentially American melodrama, led by first-time director Robert Redford. Ordinary People (1980) was, predictably, touted as the vehicle that brought Sutherland back into the comfort zone of the ordinary.

(AP Photo/Gero Breloer)

Inspiring a new generation

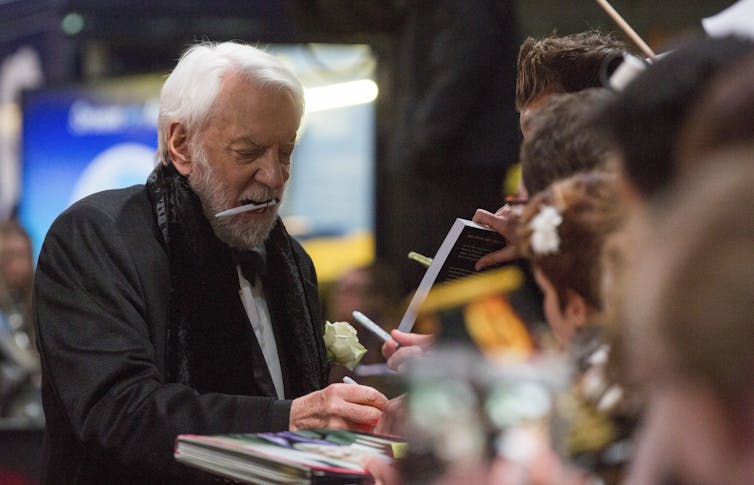

In the last years of his life, however, we might say Sutherland was returning to his political aspirations of the ’70s, hoping to move a younger generation to take over where his own generation had left off.

His tyrannical Coriolanus Snow in The Hunger Games series represented a return to the fascist individual, meant to mirror the fascistic potential in anyone.

In an interview with The Guardian in California, he expressed hope that his youthful audiences would “‘take action because it’s getting drastic in this country,” referring to a range of issues from corporate tax dodging, racism, the Keystone oil pipeline and denying food stamps to “starving Americans.”

“It’s not right,’” he said.

The post “In Donald Sutherland’s 1970s career, the personal and political met in European ‘auteur’ films” by Jean Walton, Professor Emeritus, Department of English, University of Rhode Island was published on 06/30/2024 by theconversation.com