Christof Koch, a leading researcher on consciousness and the human brain, has famously called the brain “the most complex object in the known universe.” It’s not hard to see why this might be true. With a hundred billion neurons and a hundred trillion connections, the brain is a dizzyingly complex object.

But there are plenty of other complicated objects in the universe. For example, galaxies can group into enormous structures (called clusters, superclusters, and filaments) that stretch for hundreds of millions of light-years. The boundary between these structures and neighboring stretches of empty space called cosmic voids can be extremely complex.1 Gravity accelerates matter at these boundaries to speeds of thousands of kilometers per second, creating shock waves and turbulence in intergalactic gases. We have predicted that the void-filament boundary is one of the most complex volumes of the universe, as measured by the number of bits of information it takes to describe it.

This got us to thinking: Is it more complex than the brain?

So we—an astrophysicist and a neuroscientist—joined forces to quantitatively compare the complexity of galaxy networks and neuronal networks. The first results from our comparison are truly surprising: Not only are the complexities of the brain and cosmic web actually similar, but so are their structures. The universe may be self-similar across scales that differ in size by a factor of a billion billion billion.

The task of comparing brains and clusters of galaxies is a difficult one. For one thing it requires dealing with data obtained in drastically different ways: telescopes and numerical simulations on the one hand, electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and functional magnetic resonance on the other.

It also requires us to consider enormously different scales: The entirety of the cosmic web—the large-scale structure traced out by all of the universe’s galaxies—extends over at least a few tens of billions of light-years. This is 27 orders of magnitude larger than the human brain. Plus, one of these galaxies is home to billions of actual brains. If the cosmic web is at least as complex as any of its constituent parts, we might naively conclude that it must be at least as complex as the brain.

The total number of neurons in the human brain falls in the same ballpark of the number of galaxies in the observable universe.

But the concept of emergence makes the comparison possible. Many natural phenomena are not equally complex at all scales. The majestic network of the cosmic web becomes evident only when the sky is surveyed over its largest extent. On smaller scales, with matter locked into stars, planets, and (probably) dark matter clouds, this structure is lost. An evolving galaxy does not care about the dance of electron orbitals within atoms, and electrons move around their nuclei without regard to the galactic system they reside in.

In this way, the universe contains many systems nested into systems, with little to no interaction across different scales. This scale segregation allows us to study physical phenomena as they emerge at their own natural scales.

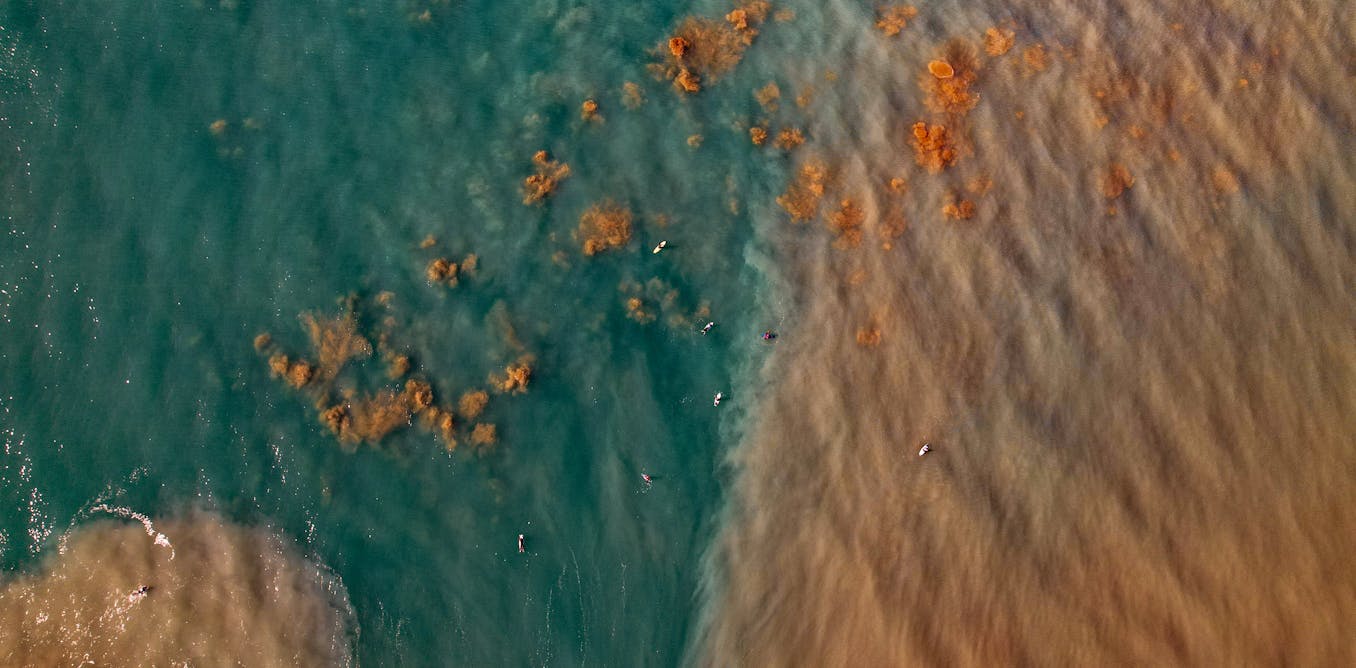

The building blocks of the cosmic web are the self-gravitating halos of stars, gas, and dark matter (whose existence has yet to be definitively proved). In total, the number of galaxies within the observable universe should be on the order of 100 billion. The balance between the accelerating expansion of the fabric of spacetime and the pull of self-gravity gives this network its spider-web-like pattern. Ordinary and dark matter condense into string-like filaments, and clusters of galaxies form at filament intersections, leaving most of the remaining volume basically empty. The resulting structure looks vaguely biological.

A direct estimate of the number of cells or neurons in the human brain was not available in the literature until recently. Cortical gray matter (representing over 80 percent of brain mass) contains about 6 billions neurons (19 percent of brain neurons) and nearly 9 billion non-neuronal cells. The cerebellum has about 69 billion neurons (80.2 percent of brain neurons) and about 16 billion non-neuronal cells. Interestingly enough, the total number of neurons in the human brain falls in the same ballpark of the number of galaxies in the observable universe.

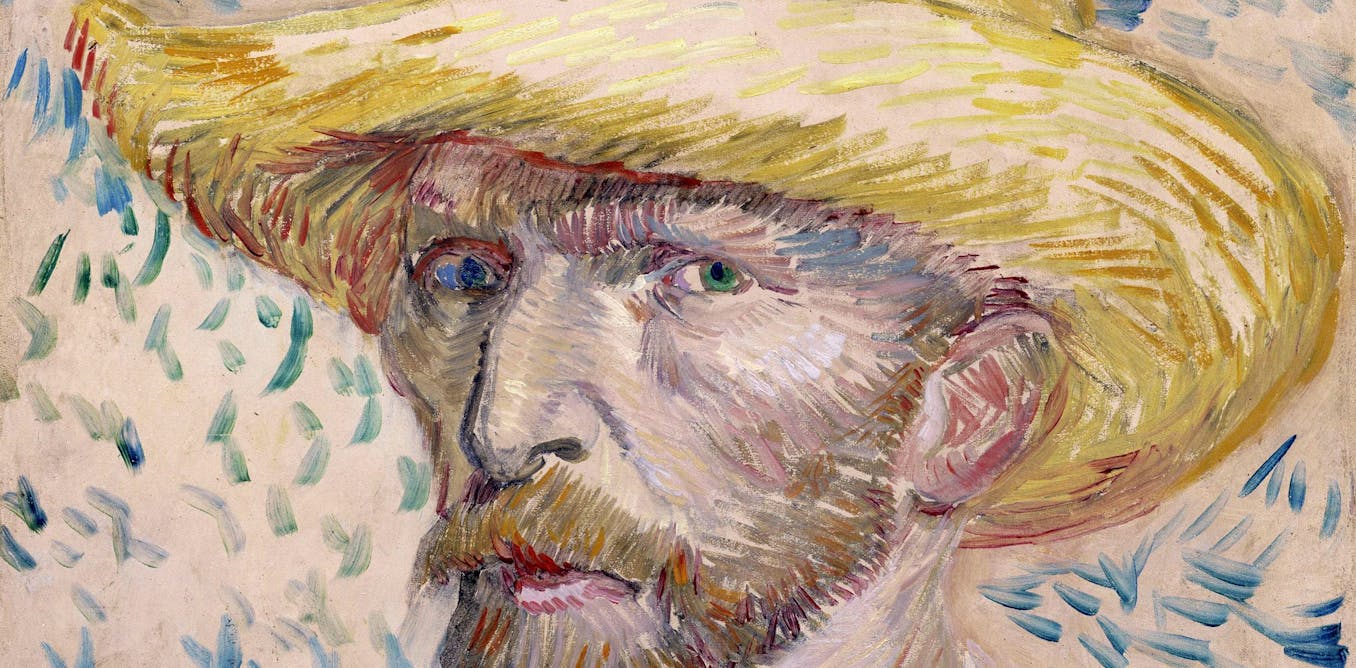

The eye immediately grasps some similarity between images of the cosmic web and the brain. We showed a simulated distribution of cosmic matter in a slice 1 billion light-years across, along with a real image of a 4 micrometers (µm)-thick slice through the human cerebellum.

Is the apparent similarity just the human tendency to perceive meaningful patterns in random data (apophenia)? Remarkably enough, the answer seems to be no: Statistical analysis shows these systems do indeed present quantitative similarities. Researchers regularly use a technique called power spectrum analysis to study the large-scale distribution of galaxies. The power spectrum of an image measures the strength of structural fluctuations belonging to a specific spatial scale. In other words, it tells us how many high-frequency and low-frequency notes make the peculiar spatial melody of each image.

A stunning message emerges: The relative distribution of fluctuations in the two networks is remarkably similar, over several orders of magnitude.

An evolving galaxy does not care about the dance of electron orbitals within atoms.

The distribution of fluctuations in the cerebellum at 0.1-1 mm scales is reminiscent of the galaxy distribution on hundreds of billions of light-years. At the smallest scales available to microscopic observation (about 10 µm), it is the morphology of the cortex that more closely matches the one of galaxies, on scales of a few hundreds of thousands of light-years.

By comparison, the power spectra of other complex systems (including projected images of clouds, tree branches, and plasma and water turbulence) are quite dissimilar from that of the cosmic web. The power spectra of these other systems display a steeper dependence on scale, which may be a manifestation of their fractal nature. This is particularly striking for the distribution of branches in trees and in the pattern of clouds, both of which are well known for being fractal-like systems with self-similarity across a large variety of scales. For the complex networks of the cosmic web and of the human brain, on the other hand, the observed behavior is not fractal, which can be interpreted as evidence of the emergence of scale-dependent, self-organized structures.

As remarkable as the power spectrum comparison is, it doesn’t tell us whether the two systems are equally complex. A practical way of estimating the complexity of a network is to measure how difficult it is to predict its behavior. This can be quantified by counting how many bits of information are necessary for building the smallest possible computer program that can perform such a prediction.

One of us has recently measured how difficult it is to predict how the cosmic network evolves, based on the digital evolution of a simulated universe.1 This estimate suggests that about 1 to 10 petabytes of data are needed to describe the evolution of the entire observable universe at the scale where its self-organization emerges (or at least of its simulated counterpart).

Estimating the complexity of the human brain is much more difficult, because global simulations of the brain remain an unmet challenge. However, we can argue that complexity is proportional to intelligence and cognition. Based on the latest analysis of the connectivity of the brain network, independent studies have concluded that the total memory capacity of the adult human brain should be around 2.5 petabytes, not far from the 1-10 petabyte range estimated for the cosmic web!

Roughly speaking, this similarity in memory capacity means that the entire body of information that is stored in a human brain (for instance, the entire life experience of a person) can also be encoded into the distribution of galaxies in our universe. Or, conversely, that a computing device with the memory capacity of the human brain can reproduce the complexity displayed by the universe at its largest scales.

It is truly a remarkable fact that the cosmic web is more similar to the human brain than it is to the interior of a galaxy; or that the neuronal network is more similar to the cosmic web than it is to the interior of a neuronal body. Despite extraordinary differences in substrate, physical mechanisms, and size, the human neuronal network and the cosmic web of galaxies, when considered with the tools of information theory, are strikingly similar.

Does this fact tell us something profound about the physics of emergent phenomena in the two systems? Maybe. But we must take these findings with a grain of salt. Our analysis has been limited to small samples taken with very different measurement techniques.

Also, our analysis doesn’t point to a dynamical similarity among these systems. A model of how information flows across spatial scales and time in the two systems will be the crucial test. This is already feasible for the cosmic web through numerical simulations. For the human brain we have to rely on more global estimates, usually derived from smaller portions that are then scaled upward. In the near future we aim at testing these concepts in more sophisticated numerical models of the human brain.

Programs like the Human Brain Project, designed to simulate an entire human neuronal network, and the Square Kilometer Array, the biggest enterprise ever in radio astronomy, will help us fill in some of these details and understand whether the universe is even more surprising than we thought.

1. Vazza, F. On the complexity and the information content of cosmic structures. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 465, 4942-4955 (2017).

This article The strange similarity of neuron and galaxy networks is featured on Big Think.

The post “The strange similarity of neuron and galaxy networks” by Franco Vazza, Alberto Feletti was published on 12/05/2023 by bigthink.com