When summer turns up the heat, cities can start to feel like an oven, as buildings and pavement trap the sun’s warmth and vehicles and air conditioners release more heat into the air.

The temperature in an urban neighborhood with few trees can be more than 10 degrees Fahrenheit (5.5 Celsius) higher than in nearby suburbs. That means air conditioning works harder, straining the electrical grid and leaving communities vulnerable to power outages.

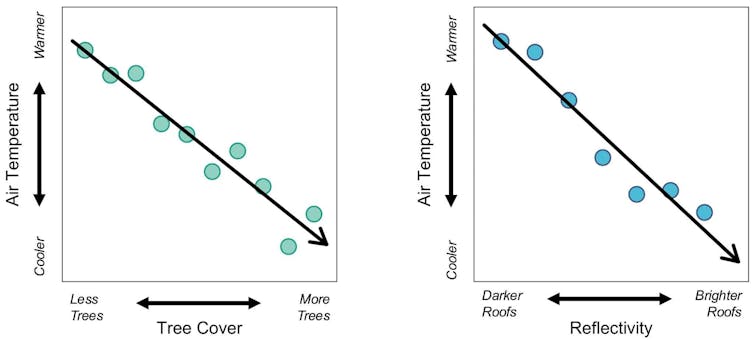

There are some proven steps that cities can take to help cool the air – planting trees that provide shade and moisture, for example, or creating cool roofs that reflect solar energy away from the neighborhood rather than absorbing it.

But do these steps pay off everywhere?

We study heat risk in cities as urban ecologists and have been exploring the impact of tree-planting and reflective roofs in different cities and different neighborhoods across cities. What we’re learning can help cities and homeowners be more targeted in their efforts to beat the heat.

The wonder of trees

Urban trees offer a natural defense against rising temperatures. They cast shade and release water vapor through their leaves, a process akin to human sweating. That cools the surrounding air and reduces afternoon heat.

Adding trees to city streets, parks and residential yards can make a meaningful difference in how hot a neighborhood feels, with blocks that have tree canopies nearly 3 F (1.7 C) cooler than blocks without trees.

NASA/USGS Landsat

But planting trees isn’t always simple.

In hot, dry cities, trees often require irrigation to survive, which can strain already limited water resources. Trees must survive for decades to grow large enough to provide shade and release enough water vapor to reduce air temperatures.

Annual maintenance costs – about US$900 per tree per year in Boston – can surpass the initial planting investment.

Most challenging of all, dense urban neighborhoods where heat is most intense are often too packed with buildings and roads to grow more trees.

How cool roofs can help on hot days

Another option is “cool roofs.” Coating rooftops with reflective paint or using light-colored materials allows buildings to reflect more sunlight back into the atmosphere rather than absorbing it as heat.

These roofs can lower the temperature inside an apartment building without air conditioning by about 2 to 6 F (1 to 3.3 C), and can cut peak cooling demand by as much as 27% in air-conditioned buildings, one study found. They can also provide immediate relief by reducing outdoor temperatures in densely populated areas. The maintenance costs are also lower than expanding urban forests.

AP Photo/Matt Rourke

However, like trees, cool roofs come with limits. Cool roofs work better on flat roofs than sloped roofs with shingles, as flat roofs are often covered by heat-trapping rubber and are exposed to more direct sunlight over the course of an afternoon.

Cities also have a finite number of rooftops that can be retrofitted. And in cities that already have many light-colored roofs, a few more might help lower cooling costs in those buildings, but they won’t do much more for the neighborhood.

By weighing the trade-offs of both strategies, cities can design location-specific plans to beat the heat.

Choosing the right mix of cooling solutions

Many cities around the world have taken steps to adapt to extreme heat, with tree planting and cool roof programs that implement reflectivity requirements or incentivize cool roof adoption.

In Detroit, nonprofit organizations have planted more than 166,000 trees since 1989. In Los Angeles, building codes now require new residential roofs to meet specific reflectivity standards.

AP Photo/Carlos Osorio

In a recent study, we analyzed Boston’s potential to lower heat in vulnerable neighborhoods across the city. The results demonstrate how a balanced, budget-conscious strategy could deliver significant cooling benefits.

For example, we found that planting trees can cool the air 35% more than installing cool roofs in places where trees can actually be planted.

However, many of the best places for new trees in Boston aren’t in the neighborhoods that need help. In these neighborhoods, we found that reflective roofs were the better choice.

By investing less than 1% of the city’s annual operating budget, about US$34 million, in 2,500 new trees and 3,000 cool roofs targeting the most at-risk areas, we found that Boston could reduce heat exposure for nearly 80,000 residents. The results would reduce summertime afternoon air temperatures by over 1 F (0.6 C) in those neighborhoods.

While that reduction might seem modest, reductions of this magnitude have been found to dramatically reduce heat-related illness and death, increase labor productivity and reduce energy costs associated with building cooling.

Not every city will benefit from the same mix. Boston’s urban landscape includes many flat, black rooftops that reflect only about 12% of sunlight, making cool roofs that reflect over 65% of sunlight an especially effective intervention. Boston also has a relatively moist growing season that supports a thriving urban tree canopy, making both solutions viable.

Imagery © Google 2025.

In places with fewer flat, dark rooftops suitable for cool roof conversion, tree planting may offer more value. Conversely, in cities with little room left for new trees or where extreme heat and drought limit tree survival, cool roofs may be the better bet.

Phoenix, for example, already has many light-colored roofs. Trees might be an option there, but they will require irrigation.

Getting the solutions where people need them

Adding shade along sidewalks can do double-duty by giving pedestrians a place to get out of the sun and cooling buildings. In New York City, for example, street trees account for an estimated 25% of the entire urban forest.

Cool roofs can be more difficult for a government to implement because they require working with building owners. That often means cities need to provide incentives. Louisville, Kentucky, for example, offers rebates of up to $2,000 for homeowners who install reflective roofing materials, and up to $5,000 for commercial businesses with flat roofs that use reflective coatings.

Ian Smith et al. 2025

Efforts like these can help spread cool roof benefits across densely populated neighborhoods that need cooling help most.

As climate change drives more frequent and intense urban heat, cities have powerful tools for lowering the temperature. With some attention to what already exists and what’s feasible, they can find the right budget-conscious strategy that will deliver cooling benefits for everyone.

The post “Which is best, urban trees or cool roofs?” by Ian Smith, Research Scientist in Earth & Environment, Boston University was published on 07/23/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply