Conspiracy theories captivate the imagination. They offer simple explanations for complex events, often involving secret plots by powerful groups. From the belief that the moon landing was faked to claims of election fraud, conspiracy theories shape public opinion and influence behaviour.

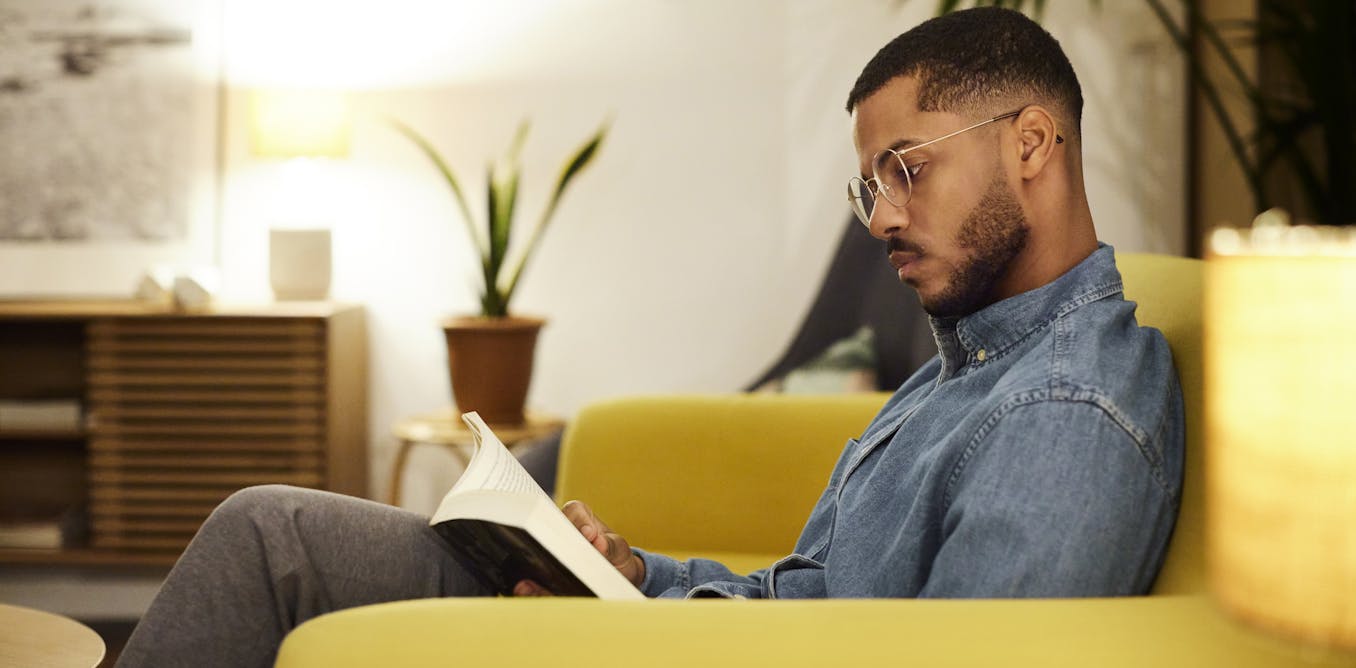

Research has explored cognitive biases, social influences and personality traits to understand why people believe in conspiracy theories. However, such research overlooks subtle day-to-day influences on conspiratorial thinking, like stress or sleep.

Our new research shows that poor sleep quality plays a key role in conspiracy beliefs.

Belief in conspiracy theories is influenced by psychological and social factors. Cognitive biases, like seeing patterns in random information, make people more prone to conspiratorial thinking.

Social influences, including social norms, also play a significant role. Personality traits such as narcissism and a preference for intuitive thinking are linked to greater conspiracy beliefs.

While these factors are well documented, our research adds another key factor: sleep quality. Poor sleep may increase cognitive biases and emotional distress, making people more likely to accept conspiratorial explanations.

The sleep factor

Sleep is crucial for mental health, emotion regulation and cognitive functioning. Poor sleep has been linked to increased anxiety, depression and paranoia – all of which are also associated with conspiracy belief.

However, sleep is rarely discussed in explanations for conspiratorial thinking.

One study found that insomnia, a clinical disorder, affects conspiracy beliefs. Building on this work, our research, published in the Journal of Health Psychology, examined how poor sleep quality, a nonclinical condition, influences conspiracy beliefs.

In the first of our studies, 540 participants completed a standard sleep quality assessment before reading about the 2019 Notre Dame cathedral fire. Half saw a conspiratorial version suggesting a cover-up, while the other half read a factual account citing an accident. The results showed that participants with poorer sleep were significantly more likely to believe the conspiracy narrative.

The second study, with 575 participants, explored psychological factors such as depression, paranoia and anger to understand how poor sleep contributes to conspiracy beliefs.

The findings confirmed that poor sleep quality was linked to conspiracy belief, with depression being the strongest link between the two. In other words, increased depression helped explain why poor sleep quality is associated with conspiratorial thinking.

Causation or correlation?

While our study links poor sleep and conspiracy belief, this doesn’t prove cause and effect. Another factor may underlie both.

For example, chronic stress or anxiety could contribute to both poor sleep and a heightened susceptibility to conspiratorial thinking. Improving mental health may be as important as better sleep.

At the same time, research on sleep deprivation shows that lack of sleep can increase anger, depression and paranoia. This could make people more vulnerable to misinformation, as seen in our research.

Future studies could use controlled experiments to examine how poor sleep contributes to conspiracy beliefs. Research shows that acute sleep deprivation increases anxiety and depression compared to normal sleep. A similar study could test whether severe sleep loss also heightens conspiracy beliefs.

GillianVann/Shutterstock

Conspiracy beliefs are not just harmless curiosities; they can have serious real-world consequences.

They have been linked to vaccine hesitancy, climate change denial and violent extremism. Understanding the factors that contribute to their spread is essential for addressing misinformation and promoting informed decision-making.

Our findings suggest that improving sleep quality may reduce conspiracy beliefs. Sleep-focused interventions, such as insomnia therapy or public health initiatives, could help counter conspiratorial thinking.

Most research on conspiracy theories focuses on thinking styles and social influences. Our study highlights sleep as a key factor, suggesting poor sleep may not only impact health and wellbeing, but also shape our worldview.

At the same time, sleep is only one piece of the puzzle.

Conspiracy beliefs likely arise from a combination of cognitive biases, social influences, emotional states and personal worldviews. Plenty of people who sleep badly would not be seduced by conspiracy theories. Future research should explore how poor sleep interacts with these other known predictors of conspiracy beliefs.

By prioritising good sleep, we can improve both our mental and physical health, while strengthening our ability to think critically and resist misinformation in an increasingly complex world.

The post “How poor sleep could fuel belief in conspiracy theories” by Daniel Jolley, Assistant Professor in Social Psychology, University of Nottingham was published on 03/12/2025 by theconversation.com

![Animals vs. Water: Hilarious Moments! 😂 [2025 Edition] – Video Animals vs. Water: Hilarious Moments! 😂 [2025 Edition] – Video](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/F1_AvAuQI5M/maxresdefault.jpg)

Leave a Reply