Plant behaviour may seem rather boring compared with the frenetic excesses of animals. Yet the lives of our vegetable friends, who tirelessly feed the entire biosphere (including us), are full of exciting action. It just requires a little more effort to appreciate.

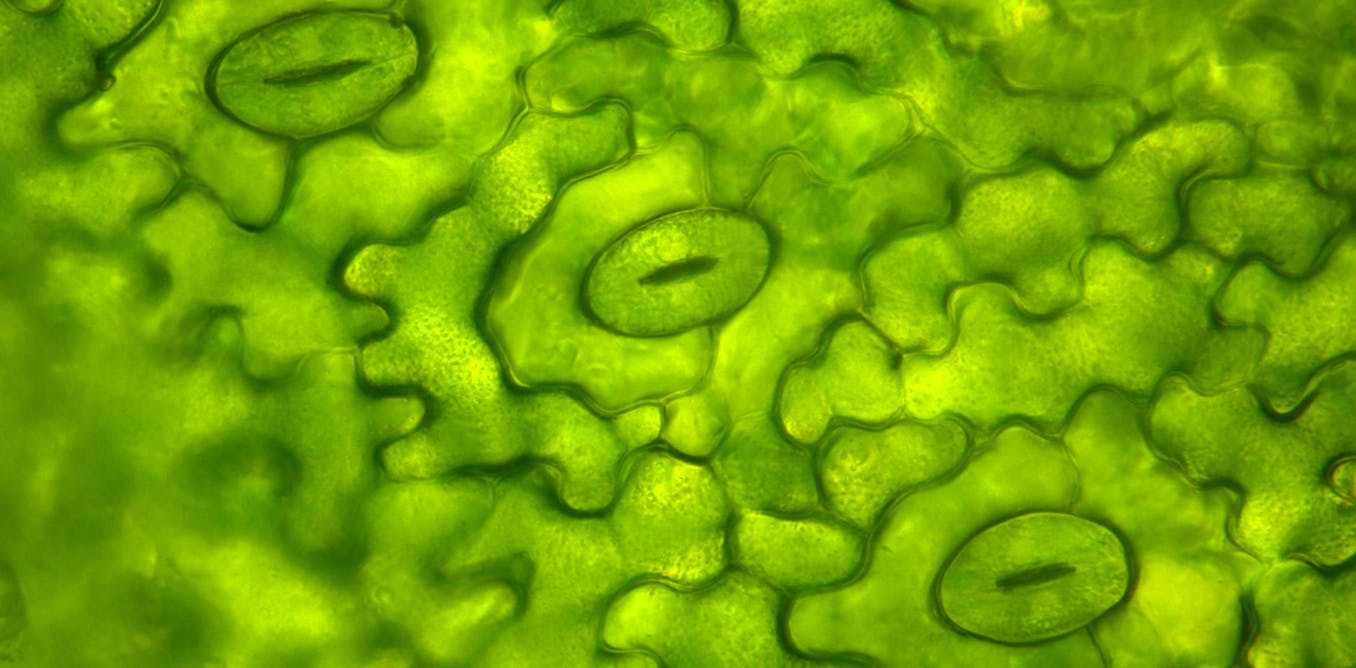

One such behaviour is the dynamic opening and closing of millions of tiny mouths (called stomata) located on each leaf, through which plants “breathe”. In this process they let out water extracted from the soil in exchange for precious carbon dioxide from the air, which they need to produce sugar in the sunlight-powered process of photosynthesis.

Opening the stomata at the wrong time can waste valuable water and risk a catastrophic drying-out of the plant’s vascular system. Almost all land plants control their stomata very precisely in response to light and humidity to optimise growth while minimising the damage risk.

How plants evolved this extraordinary balancing act has been the subject of considerable debate among scientists. In a new paper published in PNAS we used lasers to find out how the earliest stomata may have operated.

Tiny valves, global consequences

Much depends on the way stomata behave: plant productivity, sensitivity to drought, and indeed the pace of the global carbon and water cycles.

However, they are difficult to observe in action. Each stomata is like a tiny, pressure-operated valve. They have “guard cells” surrounding an opening or pore which lets water vapour out and carbon dioxide in.

Artemide / Shutterstock

When fluid pressure increases inside the stomata’s guard cells, they swell up to open the pore. When pressure drops, the cells deflate and the pore closes. To understand stomata behaviour, we wanted to be able to measure the pressure in the guard cells – but it’s not easy.

Lasers, bubbles and evolution

Enter Craig Brodersen of Yale University with a newly developed microscope-guided laser. It can create microscopic bubbles inside the individual cells that operate the stomatal pore.

When Brodersen spent a sabbatical at the University of Tasmania (where I am based), we found we could determine the pressure inside stomatal cells by tracking the size of these bubbles and how quickly they collapsed. This involved theoretical calculations guided by bubble expert Philippe Marmottant, of the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Grenoble.

This new tool gave us the perfect opportunity to explore how the behaviour of stomata is different among major plant groups. The aim was to test our hypothesis that the evolution of stomatal behaviour follows a predictable trajectory through the history of plant evolution.

We argue it began with a relatively simple ancestral passive control state, currently represented in living ferns and lycophytes, and developed to a more active hormonal control mechanism seen in modern conifers and flowering plants.

Against this hypothesis, some researchers have previously reported complex behaviours in some of the most ancient of stomata-bearing plants, the bryophytes. We wanted to test this finding using our newly developed laser instrument.

400 million years of development

What we found was firstly that our laser pressure probe technique worked extremely well. We made nearly 500 measurements of stomatal pressure dynamics in the space of a few months. This was a marked improvement on the past 45 years, in which fewer than 30 similar measurements had been made.

Secondly, we found that the stomata of our representative bryophytes (hornworts and mosses) lacked even the most basic responses to light found in all other land plants.

Gondronx Studio / Shutterstock

This result supported our earlier hypothesis that the first stomata found in ancestors of the modern bryophytes 450 million years ago should have been very simple valves. They would have lacked the complex behaviours seen in modern flowering plants.

Our results suggest that stomatal behaviour has changed substantially through the process of evolution, highlighting critical changes in functionality that are preserved in the different major land plant groups that currently inhabit the Earth.

How plants will survive the future

We can now say with confidence that stomata in mosses, ferns, conifers and flowering plants all behave in very different ways. This has an important corollary: they will all respond differently to the heaving changes in atmospheric temperature and water availability that they face now and into the near future. Predicting stomatal behaviour in the future will help us to predict these impacts and highlight plant vulnerability.

In terms of agricultural benefit, our new laser method should be fast and sensitive enough to reveal even small differences in the the behaviour of closely related plants. This may help to identify crop variants that use water in a more efficient or productive way, which will assist plant breeders to find varieties that better translate increasingly unpredictable soil water supplies into food.

So next time you look upon a leaf, consider the frantic pace of dynamic calculation and adjustment of millions of little mouths, reacting as your breath falls upon them. Realise that our own fate, tied to the performance of forests and crops in future climates, hangs on the behaviour of the stomata of different species. A good reason for us to understand these unassuming little valves.

The post “Plants breathe with millions of tiny mouths. We used lasers to understand how this skill evolved” by Tim Brodribb, Professor of Plant Physiology, University of Tasmania was published on 03/24/2025 by theconversation.com

Leave a Reply